SERENA GAMBA

| by Barbara Pavan |

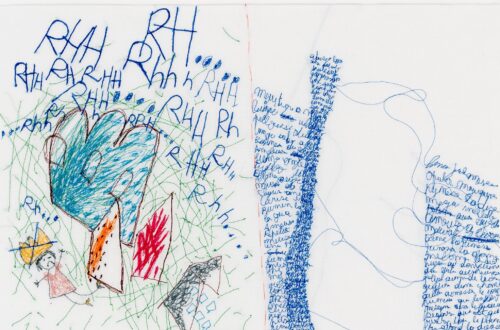

The practice of Serena Gamba (Moncalieri, 1982) is rooted in a deep reflection on painting as a space of tension between permanence and erasure, between iconic memory and semantic oblivion. Her work develops through a process of emptying and re-signifying images from the History of Art, where each reference is stripped of its original function to reveal an essential grammar, purified of superstructures and codified rhetorics. Gamba works with words, marks, and forms—not as expressive elements, but as archetypal units to be dismantled and recomposed.

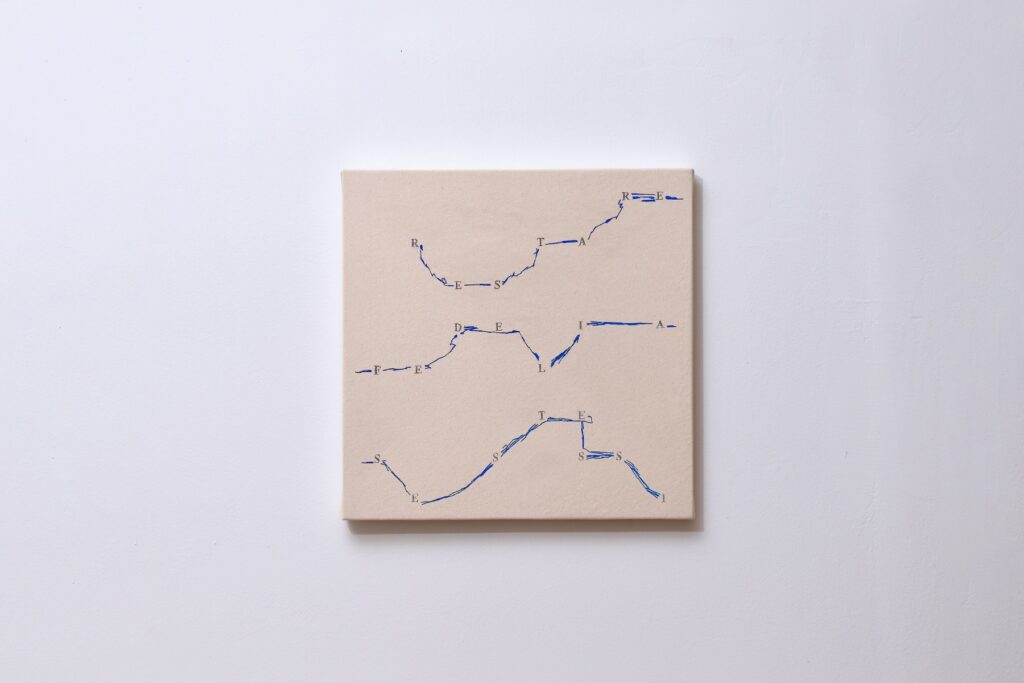

Painting, drawing, and verbal language converge in a hybrid system that takes the form of a constantly mutating visual alphabet: a lexicon of fragments, geometries, structural voids, and symbolic condensations that do not impose a reading but rather displace it. In this field of forces, the image is never final but processual, it does not represent but indicates, evokes, and leaves space.

Her works have been presented in institutional and independent contexts, often in dialogue with historical figures or peers sharing a similar language and conceptual tension. Among the most significant projects are the exhibitions Non appartengo alla terra at Casa Gramsci in Turin, Dialogo sulle parole with Alighiero Boetti at Galleria Umberto Benappi, and Dialogo 1 with Mirella Bentivoglio at NP Gallery/Martelli Fineart in Milan. She has also participated in exhibitions such as Residenze d’artista at the Rossetti Valentini School in Val Vigezzo, Pittura Italiana #1 at The Corner (Andes, NY), Senza fine né forma (Duetart Gallery), and The Soft Revolution at the Textile Museum of Busto Arsizio. Her presence is also distinct in research and experimental spaces such as Galleria Alessio Moitre in Turin, where she has taken part in several group shows tied to the Exhibi.To project. Her work has been recognized with awards such as the A Collection Prize at Art Verona 2021, consolidating a coherent and rigorous artistic path, which she told me about in this interview.

What path led you to embroidery as an artistic technique?

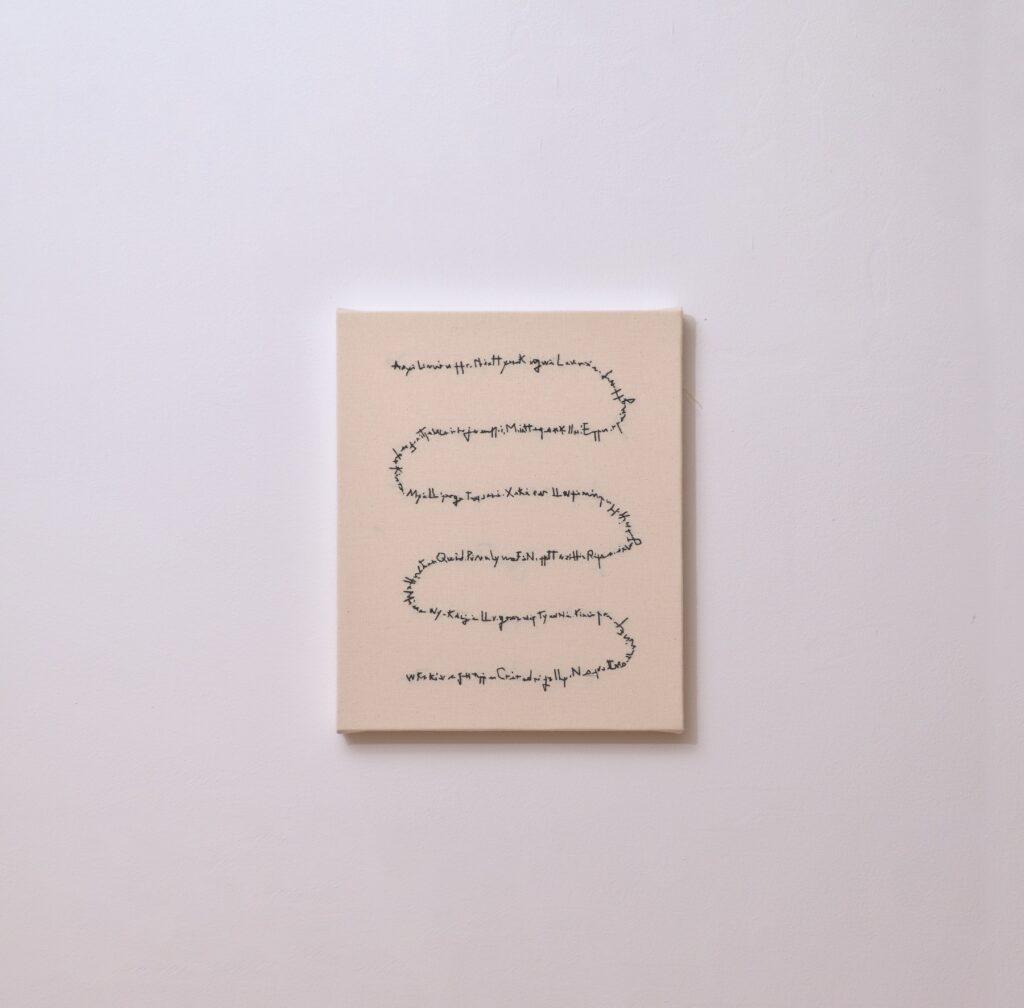

Embroidery became part of my work when I accepted, both in my research and in my life, the necessity of oblivion. I needed to find a way to embrace a technique that was both incisive and delicate, and embroidery gave me that strength and sensuality I was looking for. At first, I worked only with graphite and charcoal—essentially powdery materials, whose very essence has always expressed earthly instability. All the materials I use in my work refer to fragility, delicacy, and the temporary. I find that expressing these aspects is very poetic. Among them all, embroidery perhaps represents the most aspects simultaneously, even contrasting ones. Thread in itself is fragile, yet the persistence with which it is used allows things to hold together, to resist over time. Embroidery brings me back to stitching, and I find it astonishing that such a slow and relentless gesture can allow the creation of even incredible works, like the sail of a ship.

What is, for you, the connection between embroidery and words?

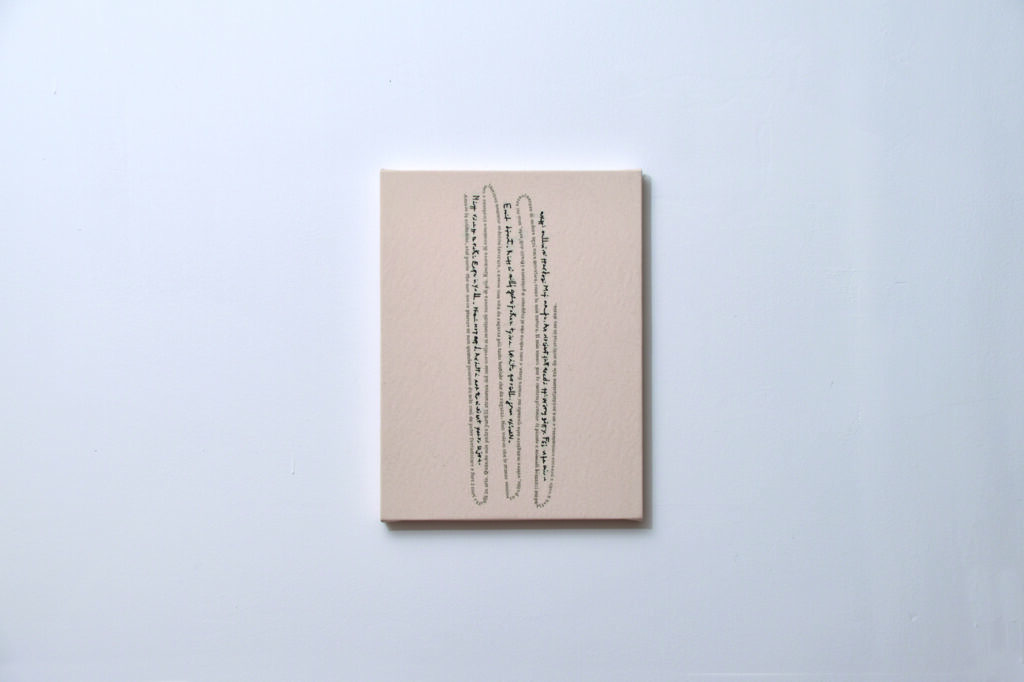

Words are life; they come alive in the mind, generating images. A word is sound, form, and color. It can be extremely abstract and return to a primordial form as a sign or transform into a drawing. It can become musical, mark a rhythm. Embroidery has allowed me to introduce what I call “dream words”—a different language that loses the weight of meaning but gains the beauty of interpretation, like when listening to or reading an unfamiliar language: by not focusing on meaning, we appreciate or understand other, less codified aspects.

How are your works conceived and developed?

My works—whether they contain words and embroidery, just words, or just embroidery—arise from research and study of the History of Art. I deeply love this approach, which allows me to keep investigating, to remember works of the past, or to pay homage to artists who have influenced my research. I often end up creating several pieces in different modes/techniques that refer to the same panel or painting. The interpretive possibilities, as well as the references that Art History offers us, are, in my opinion, endless. We could probably spend an entire lifetime studying a single work and extract countless possibilities and meanings from it.

How has your research evolved over time?

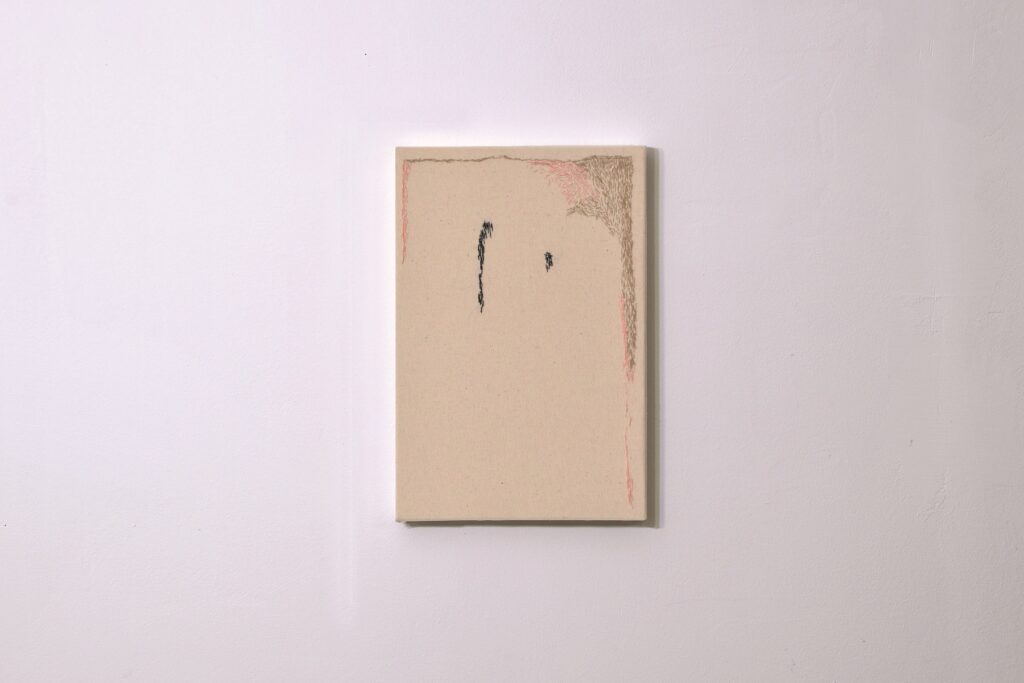

I began by generating a sort of memory archive. Initially, my intent was to find a way to remember as much information as possible regarding Art History, as if it were a kind of “family” testament (which it is, if we think of it as a collection of elements representing our culture). This “obsession” with remembering led me to use the word as a container within a container. The word to write, to memorize through a slow and repetitive process, but also as an extremely versatile tool to feel part of a culture, of a place. At a certain point, my need to remember everything gave way to the awareness that we are not made to retain everything (to control), and that forgetting (letting go) has a necessary function—terrible in some ways, but also redemptive. The moment I accepted this, oblivion entered my research, along with embroidery, and the alternation of word/meaning with word/sign and pure sign.

How would you define your artistic research and practice today?

I would define it as something that requires time—both to create and to experience. Over the years, in exhibitions and through the people I’ve met—visitors, collectors—I realized that one thing “connects” us: the will and need to carve out a moment for oneself. My works demand a moment of intimacy dictated by many factors: the pause to read, to enter the story, to understand its interpretive key, to let it resonate. My work doesn’t “shout,” either in concept or technique. This immersion and closeness require an effort, one that today’s world is erasing with the rapid pace of content flows imposed upon us, with attention spans now reduced to mere seconds. I love the peace that certain places or works emanate and demand; for me, silence, for instance, is a form of respect—I find it beautiful. I would very much like for my entire body of work to emanate this idea.

What does being an artist mean to you?

For me, being an artist is the only way to stay in the world—but at the same time, it is also an act of resistance and courage, at least in Italy.

We live in a technological era, and technology is the measure of the speed of our time. How does a slow, ancient medium like embroidery relate to contemporaneity?

It doesn’t, for me. It is the mirror of a mode that has passed, that belongs to the 20th century, the century I was born into and to which I am naturally connected. But that doesn’t mean it’s old — it simply responds to different paradigms. And this makes it fascinating and poetic. For me, it is a model not to be forgotten, because it follows a rhythm that feels more natural to me. My work also uses technology — I live in this time and therefore take advantage of systems that speed up certain processes, experiences, movements, the everyday — but I’ve noticed on more than one occasion that too much technology and “super-speed” alienates and de-personalizes me.

Can you tell me about your recent exhibition project at Casa Gramsci – “Non appartengo alla terra” – made up of a body of different works?

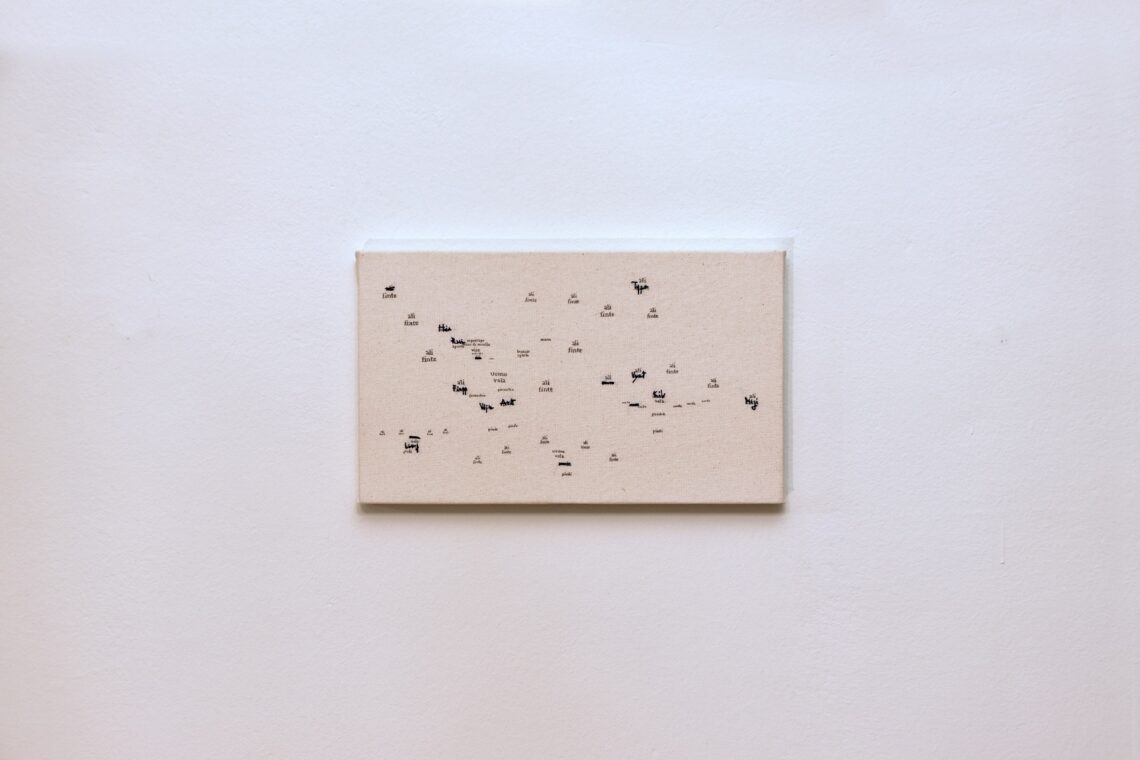

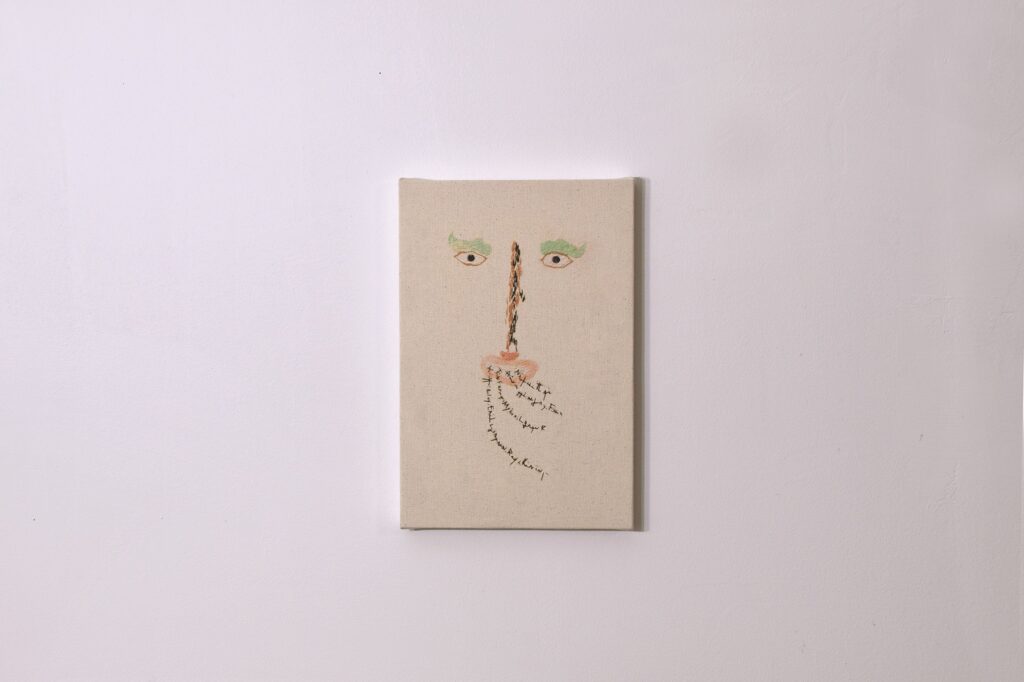

The exhibition at Casa Gramsci, curated by Lunetta11 and NP ArtLab, was conceived to dialogue with a space that is, in itself, already a work of art, and therefore not simple. One had to enter on tiptoe, engaging without imposing. The show refers to a journey I took 11 years ago in the United States. On that occasion, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I fell in love with a small panel just a few centimeters large—but immense in impact. A panel that speaks precisely of a journey: in this journey, the characters, almost indistinguishable, merge into one another in perfect rhythm. This small panel is a marvelous work by Sassetta: Il viaggio dei Magi (The Journey of the Magi). At Casa Gramsci, The Journey of the Magi became a matrix open to multiple readings and re-readings, depending on the various symbols it carries. The Magi become “magi able to read signs and stars,” creating languages and alphabets formed through different approaches—whether sign, form, color, word, or meaning. The body of works was thus made up of three “organisms”: a large hanging canvas onto which chromatic forms in wool were stitched, where Il viaggio dei Magi (The Journey of the Magi became an abstract memory of shape and color—learning to read form and color. Following that, a small canvas, “Lettura e obnubilamento de il viaggio dei magi (Reading and Obfuscation of The Journey of the Magi)”, matching the dimensions of the original; here, the word came alive, taking on form and color; intimately, they acquired different meanings, offering a new vision and interpretation.

Finally, three antique bricks painted in tempera evoked, through poetic phrases, some of the colors present in Sassetta’s painting, thus allowing interpretative and perceptive freedom.

What are you working on right now?

I’m working on an exhibition that will be held in Belgrade at the end of the year, where several of my works will be in dialogue with those of other female artists.

What is art for, Serena?

That’s a very complex question because it can have many answers depending on the context and on what is meant by “Art.” Lea Vergine said: “Art is not necessary, it is the superfluous. What we need to be happy, or at least less unhappy, is the superfluous.”

I can tell you what art means to me. I believe that everyone feels they have a place in this world by doing certain things; for me, art is my way of staying in the world.