THE AESTHETICS OF FRAGILITY: AMY USDIN

| by Barbara Pavan |

With a BFA in Graphic Communications from Washington University, St. Louis, Amy Usdin spent years as an art director before starting her studio practice in 2018. She has exhibited widely, including prestigious surveys representing the diversity and breadth of contemporary craft and fiber art, closing 2025 with a solo show at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in MN. Recognition includes publication in Fiber Art Now’s Excellence in Fibers, multiple awards from the Surface Design Association, and multiple grants from the Minnesota State Arts Board and Metropolitan Regional Arts Council. Usdin is a 2024 recipient of the Stone and DeGuire Contemporary Art Award from Washington University, the 2024/2025 MCAD-Jerome Fellowship, and the 2025-2028 Jerome Hill Artist Fellowship.

Amy Usdin needle-weaves physical and psychological landscapes onto worn fishing nets and horse fly nets.

As worn imperfections meld with the new threads, the transformation becomes part of a continued narrative informed by the familial moments and unexpected associations the nets evoke. Their ragged characteristics encourage empathic response, with the reconstructed objects acting as metaphor for themes that weave past to present and each of us to another.

2020

animal and plant fibers on vintage horse fly nets 56 x 42 x 5.5 inches

For Usdin, these nets are more than materials; they are deeply symbolic. She first began working with horse fly nets during a time when she was caring for her elderly parents, whose declining health made her reflect on the fragility of life. This parallel between tending to worn objects that had outlived their purpose and providing care for loved ones nearing the end of their lives became a powerful foundation for her work.

The act of reclaiming these nets is both personal and profound. By weaving within the fixed borders of these fragile, timeworn objects, Usdin found a way to reconcile layers of her own history. As social creatures, horses are capable of human-type emotion from joy and abandon to anxiety and fear. Like intimate hand-me down clothing, their nets can carry that emotion. Moreover, they draw out her stories which become physically embodied in her knotted and woven forms. Reworking these obsolete nets through a personal lens—that of compliance, erasure, renewal, motherhood, eldercare, and aging—she reflects on her own changing relevance.

Dismount Left (left) 2019cotton, linen, paper, silk, and wool on vintage rope horse fly net 31 x 15 x 6 inches. The Weight of It (right) 2020 animal and plant fibers on vintage horse fly nets 75 x 24 x 7 inches

When Usdin began her practice, deep in the throes of eldercare, she found it hard to see beyond her own world. The confines of the early pandemic marked a turning point in her artistic vision, shifting her focus outward. She moved from personal grief to a more universal sense of mourning with her fly net sculptures reflecting collective frustration, loneliness, and separation. The forced isolation invited exploration of the duality of nets with the blurred boundaries between protection and entrapment, and the ways we perceive security.

It was during this time that she found herself drawn to fishing nets. Reminiscent of those made and repaired since the beginning of humankind, they offer a point of shared humanity, something she clung to in the stillness of the lockdown that forced a complicated relationship to the passage of time. The nets continue to provide empathetic bases on which to process contemporary biographies.

2021

wool on vintage rope and canvas horse fly net 54 x 17 x 6 inches

Usdin’s sculptures are inherently tactile, inviting viewers to engage with their textures and forms. Despite the deeply autobiographical origins of much of her work, she emphasizes that her work extends beyond her own experiences. Vaguely anthropomorphic, the work acknowledges human vulnerabilities and complexities through which she hopes viewers can make their own associations. She finds it gratifying when others recognize her intent, but she is equally delighted when they discover entirely new meanings in the threads and knots of her work.

Her creative process is intuitive and shaped by the materials themselves. While each piece begins with a specific memory or association, the structure of the nets inevitably influences its final form. The process is fluid, a constant negotiation between her initial vision and the unpredictable constraints of the material. The aged ropes are often unpredictable, with broken and irregular structures that make them difficult to manipulate. Because the nets have a built-in fixed structure, every finished section alters the possibilities for what comes next, gradually narrowing the options as the work moves toward completion. This creates waves of uncertainty as she moves through each piece, constantly adapting her approach to accommodate the limitations of the nets. This dynamic interplay between intention and adaptation gives each sculpture its unique shape and character.

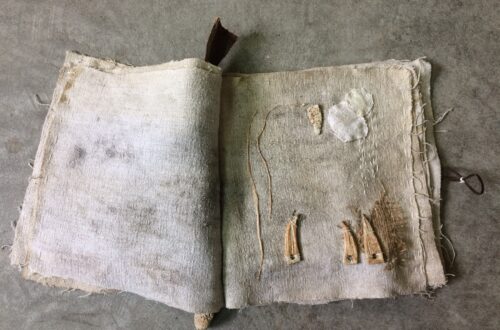

wool, linen, wax

10.From the Object Series 2025

wool, linen, wax

wool, linen, wax

The act of weaving itself is deeply meditative, offering Usdin a way to slow down and reflect. Textile techniques like sewing, mending, and needle-weaving are inherently time-consuming, requiring repetitive gestures that create space for mindfulness. For Usdin, this process is not only a creative endeavor but also a therapeutic one. “The slow process of needle-weaving allows room for epic stream of consciousness—or room to think about nothing at all,” she explains. The repetitive motions of her craft bring her solace in challenging times.

Her artistic journey began in the 1970s, when she was a teenager inspired by the fiber art movement and its now-iconic pioneers. While her early explorations with textiles laid the foundation for her current work, she initially pursued a career in commercial art direction, setting aside her passion for fiber art for decades. This changed profoundly when she attended Sheila Hicks’ retrospective at the Pompidou some forty years later. The experience was transformative, rekindling her love for textile art and reaffirming her desire to return to this medium.

animal and plant fibers on vintage horse fly nets 72 X 28 X 15 inches

Her work continues to evolve. In a technical shift, Usdin has spent the past year exploring alternate modes of construction to create workto sit in conversation with her continuing net sculptures, providing thematic depth. Recently, this has included a series of pulled warp objects that flesh out her installation, Picnic at Dead Horse Bay. Dead Horse Bay in Brooklyn, NY, is the site of a poorly capped midcentury landfill that continually blankets the beach with the remnants of neighborhoods torn apart by eminent domain. These loom-woven forms echo the shapes within the installation’s panels, giving dimension to the fragments of those disrupted lives. Altogether, they tell a story of revolving histories, that the past often resurfaces unexpectedly, often consequentially.

animal and plant fibers on vintage fishing nets 94 x 72 x 78 inches, variable

animal and plant fibers on vintage fishing nets 94 x 72 x 78 inches, variable

Photo credit: Amy Lamb, NativeHouse Photography

Though first differentiating between physical and psychological landscapes in her work, she currently considers how bodies of land and bodies of flesh coalesce, whether the trauma they endure is inevitable versus imposed. This slight shift in thinking was influenced by a 2023 residency in Iceland that continues to inform the trajectory of her practice.

Two years after the death of her mother, Usdin was still grappling with what she viewed as failure to mitigate her harrowing end, exacerbated by pandemic-strapped medical and social systems. She unexpectedly found a sense of closure walking among Icelandic lava fields where she began to connect that scars in the landscape mirror our own. This resulted in the floor sculpture Mother/Earth, which finds anthropomorphic form in the hardened landscape.

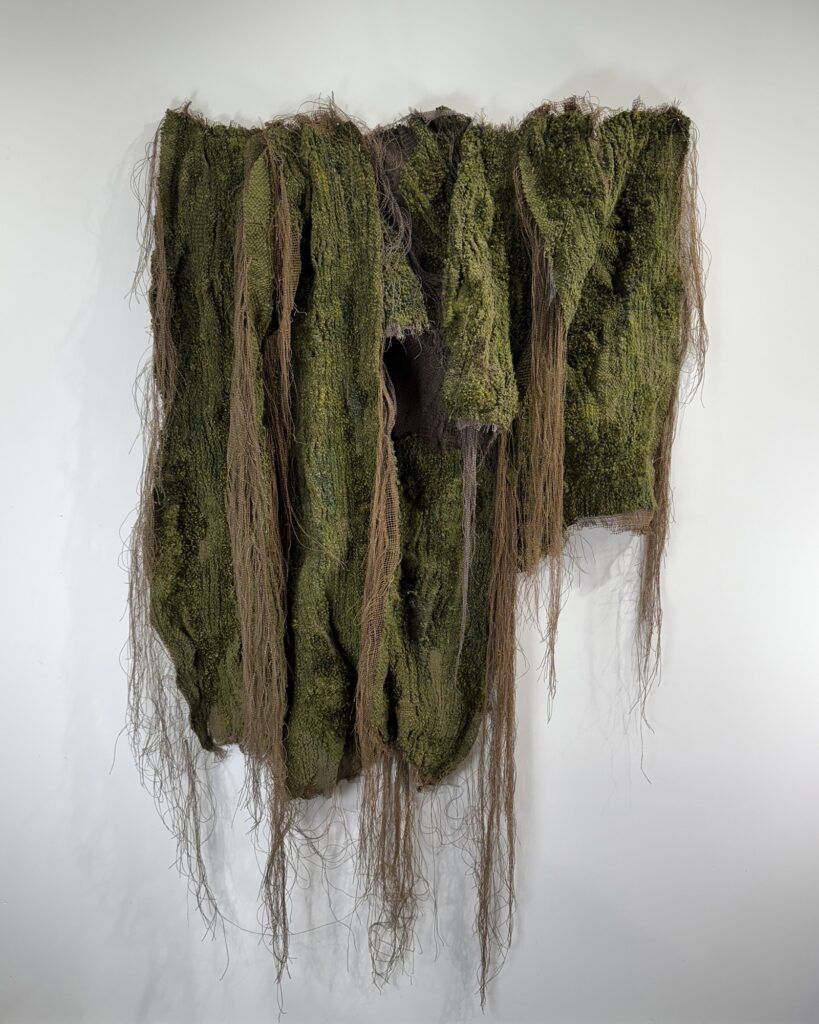

She is currently developing panels for a large-scale sculpture that reflect the sheet moss falling from sheer cliffs in Iceland, burdened by the weight of water and gravity.

For Usdin, weaving fills a need to document scars aesthetically, not just for the undignified end through which she shepherded both parents but for past experiences and traumas that have clarified themselves through the act of weaving.

2025

animal fibers on vintage fishing nets

63 x 36 x 6 inches

plant and animal fibers on vintage fishing net

9 x 78 x 78 inches